03.1 - C14H-2025-0122 - Application — original pdf

Backup

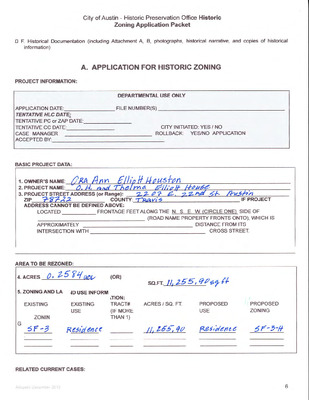

F.3, F.4, F.6, F.9 – Historical Documentation O. H. and Thelma Elliott House – 2207 E. 22nd Street, Austin, TX 78722-2115 The O.H. and Thelma Elliott House at 2207 E. 22nd Street meets the standards as an Austin Historic Landmark in two of the five criteria for significance: Architecture and Historical Associations. Built in 1954, the early Ranch Style house is more than 50 years old and reflects the historic period and architectural trends in which it was built and achieved significance. The house clearly embodies the distinguishing characteristics of a recognized architectural style (Ranch). It retains a high degree of the seven aspects of historic and architectural integrity set out by the National Register of Historic Places in Bulletin 16 (integrity of location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association). More importantly, the house is associated with husband and wife, O. H. and Thelma Elliott, a “power couple” of segregated East Austin who were at the forefront of Civil Rights-era political and educational movements and Great Society programs in the city from the 1940s through the 1970s. The designation criteria for significance is fully addressed and supported in the following narratives. Criterion: Architecture Architectural Description Construction: The 2200 block of E. 22nd Street was not developed until after World War II. In 1952, Brown and Root Construction, Inc. opened and paved the previously closed street between Coleto and Chestnut Streets; development in the block commenced soon afterward. In December 1954, realtor Andy Anderson placed an advertisement in the Austin American newspaper for an “Open House.” The ad was specifically geared to attract “Colored” people as noted in the announcement. The ad described the house as a “lovely frame and cutstone home at 2207 E. 22nd Street, 3 bedrooms, 2 all tile bathrooms, hardwood floors, car port, den.” The 1,700 square foot Ranch style house in this newly-opened section of East Austin was a modern departure from the early twentieth century bungalows, shotgun houses, and “classical box” houses in the so-called “Colored District” south of Manor Road. Anderson added Arthur Park’s name as the contractor in the notice, an indication that his work was known and respected. Arthur Parks was a carpenter and contractor who worked in Austin from c. 1949 through the 1970s. He appears to have been well-known in East Austin; his work on the Mid-century Modern house for Mr. and Mrs. John King at 2400 Givens Avenue in 1960 was lauded as “Another Arthur Parks Production,” in a newspaper notice for their open house.1 Parks also served as general contractor for a major remodel of King-Tears Mortuary designed by architect John Chase in 1971.2 Both buildings are still extant. 1 “Mr. and Mrs. John T. King Announce “Open House” (Another Arthur Parks Production), The Austin American, February 6, 1960: 11). 2 “Mortuary Sets Open House,” The Austin American, May 13, 1971: 27). 1 General Description: The O.H. and Thelma Elliott House is a one-story Ranch Style house with a low- pitched cross-gabled roof, a shallow, irregular U-shaped footprint, and asymmetrical massing. The house rests on a pier and beam foundation; it has a cement stucco skirt punctuated with open-work concrete vents at regular intervals for air flow. The primary (street-facing) façade is composed of three unequal- sized bays: two forward-projecting wings on either side of the house with a slightly recessed porch set between them under the main roof. Each bay features large windows configured to appear as “picture” windows with good views of the front yard and streetscape. At the rear of the house is a medium-pitched front-gable wing with full-height sliding glass doors that open onto a concrete patio. Site and Foundation: The Elliott House lies on a slightly sloping site with the west side of the building at grade level and the east side rising to about 1½ feet above grade. A concrete sidewalk runs the width of the lot; a curved concrete walkway leads to the front steps. The xeriscape yard is covered in small, gravel- like white stones and dotted with drought-resistant flowering plants, including a large prickly pear cactus. A concrete driveway leads from the curb cut to an original free-standing carport supported by metal poles with an attached utility shed at the rear. A chain link fence encloses the rear-side and back yards. House Form/Body: The body of the house is a broad, side-gabled volume that spans most of the lot width. A front-gabled forward-projecting wing extends from the east side of the main side-gabled roof; a second, smaller shed-roofed wing projects forward beneath the slope of the side-gabled roof on the west. A front- gabled rear wing extends from the side-gabled volume to the patio and back yard on the south side of the house. At the rear east side of the front-gabled wing lies a single-wide 12’ x 70’ Fleetwood Mobile Home built and installed on the site in 1970; the mobile home is considered and taxed as personal property by the Travis County Appraisal District. Porch and Entrance: A shallow, partial-width front porch supported by full-height floral-patterned wrought iron posts is set between the two front-gabled wings and sheltered under the main shed roof. Three concrete steps lead to the porch and front door; the door features an arched window with faux leaded glass in the upper panel. Fenestration: Fenestration on the primary façade consists of three sets of aluminum windows: large, paired 1/1 double hung windows in each of the front-gabled wings and a tripartite “picture” window composed of a central single-lite window flanked by two narrower 1/1 windows. On the east façade are 2 two large 1/1 aluminum windows and two small 1/1 bathroom windows. There are no windows on the west façade except for a small window box into the kitchen. The rear (south) façade is dominated by a set of aluminum frame sliding glass doors that open from the den onto a concrete patio. Siding: The frame house is clad in aluminum lap siding. On the front façade, a band of rusticated cast stone in regular courses stretches from beneath the windowsills to the top of the foundation skirting; the secondary east and west facades are entirely aluminum lap siding without cast stone accoutrements. The roof is composition shingle and has aluminum gutters and downspouts. Setting: The O.H. and Thelma Elliott House occupies a large residential lot at 2207 E. 22nd Street, between Coleto and Chestnut Streets, in East Austin. Except for a modern multi-unit two-story condominium at the corner of Coleto, the block is composed of one-story single-family houses dating to the early post-World War II period. At that time, this part of the city was considered the segregated “Negro” or “Colored” District, i.e., east of the East Avenue, now IH-35, south of Manor Road. All of the original families on the block were African American; it has since become fully integrated. Despite the recent influx of ultra-modern houses in the general area, the 2200 block of E. 22nd Street retains its historic neighborhood character and building fabric to the extent that it conveys a good sense of the postwar suburban development era in which it was built. Architectural Analysis and Assessment Ranch Style: [Virginia McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses, 2018] The O. H. and Thelma Elliott House is analyzed and evaluated in accordance with the work of Virginia Savage McAlester, one of the most-widely respected experts in the classification and analysis of historic residential architecture. According to Ms. McAlester, the date range for the Ranch Style extended from c. 1935 to 1975. She described the identifying features of the Ranch Style as “Broad one-story shape; usually built low to ground; low-pitched [gabled] roof without dormers; commonly with moderate-to- wide roof overhang; front entry usually located off-center and sheltered under main roof of house; garage typically attached to main façade; a large picture window generally present; asymmetrical façade.” The description applies to the O.H. and Thelma Elliott House in all respects except the garage; however, many Ranch Style houses – especially in hot climates – had free-standing carport/sheds as in the Elliott House. Ms. McAlester went on to identify four principal subtypes of Ranch style houses: hipped roof, cross- hipped roof, side-gabled roof, and cross-gabled roof. She stated that about 40 percent of Ranch Style houses are cross-gabled, with a “broad side-gabled form, with a long roof ridge parallel to the street, and a single prominent front-facing gable extension. Occasionally a second such gable is present.” The O.H. and Thelma Elliott House exemplifies the cross-gabled subtype of Ranch Style houses, with its long, low side-gabled form punctuated by a front-gabled projection on the east and secondary front-gabled wing on the west side of the primary façade. Ms. McAlester further stated that “more than 50 percent of Ranch houses have at least one picture window on the front façade, and some examples have more.” This was especially true of early postwar Ranch houses, including the Elliott House which has a main tripartite window (wide center light flanked by two narrower lights), as well as picture windows in each of the gables on the primary façade. Many 3 early postwar Ranch houses like the Elliott House featured pre-manufactured metal (aluminum, steel, or bronze) windows of varying sizes and shapes but with the same material and design family. The Elliott House meets this description: most of its windows are 1/1 double-hung aluminum sash on both the primary and secondary facades. An exception is the near full-height aluminum frame sliding glass doors on the rear (south) façade, that open into the den. Front entries on Ranch Style houses are almost always off-center and sheltered by the main roof and overhanging eaves. They are typically positioned at the juncture of the long wall and front-projecting gable which offers greater shelter from the rain. The Elliott House is a good example of this type. Like about 50 percent of Ranch Style houses, the Elliott House has a partial width front porch contained under the main roof where is relatively inconspicuous. Originally, the porch on the Elliott House spanned the width of the long wall but when a second front-gabled wing was added on the west side of the house, the porch became nestled between the two gable ends. While some Ranch Style porch supports are simple wood posts, others are wrought iron rendered in vine or floral patterns such as those on the Elliott House, which has two full-height floral-design posts and alternating floral and twisted railings with twisted handrails. Builders of Ranch Style houses frequently added bits of traditional detailing, the most common of which were decorative – inoperable – window shutters like those on the Elliott House’s main façade. Architectural Integrity The house retains exceptional architectural integrity to the historic period, i.e. a dining room addition on the front west side of the house and aluminum siding were added in the period of significance, before 1961; thus, they possess significance in their own right. The plan and footprint of the house, including the den at the rear, roof form and pitch, fenestration pattern, siding profile, front porch and rear terrace all date to the period of significance. Architectural Significance The O.H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott House is an excellent example of the Ranch style, one of the most popular and enduring architectural styles for residential buildings in American history. The Ranch style house epitomizes the postwar “baby boom” era in its modern form, functional plan and interior layout, and absence of nonessential details and embellishments that characterized earlier architectural styles for domestic construction. The Elliott House reflects modern Ranch style traits in its single-story construction, low-pitched gable roof, shallow front porch and larger, more secluded rear terrace, detached carport, lack of extraneous ornament and simplified fenestration pattern. Even the application of aluminum siding which occurred during the historic period is emblematic of the modern era in which it was sold to consumers for energy efficiency and low maintenance. The Elliott House is largely intact to the historic period in its Ranch style plan, roof form and pitch, fenestration pattern, and appurtenant features. Thus, it embodies the principal characteristics of an iconic architectural style in postwar America. 4 Criterion: Historical Associations The mid-century Ranch style house at 2207 E. 22nd Street is closely associated with husband and wife, O. H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott, the original “power couple” of segregated East Austin who were at the forefront of Civil Rights-era political and educational movements and Great Society programs in the city from the late 1930s through the 1970s. O. H. Elliott Dr. Ora Herman – O. H. – Elliott was born in Hope, Arkansas in 1909. He grew up in Muskogee, Oklahoma where he graduated from high school then received both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from the University of Kansas.3 Though not a segregated college, per se, Black male students were made to sleep on the outside sleeping porch, a reminder that racism existed not just in the South but throughout the country at that time. 4 After earning his graduate degree, Elliott served as the business manager of Clark College, a Methodist university in Atlanta, Georgia and the first historically Black college and university (HBCU) established in the southern United States. In 1935, Elliott moved to Austin to serve as business manager of Samuel Huston College; upon the death of the school’s president, Karl Everett Downs, he also served as Interim President of the college.5 When Elliott started working at Samuel Huston, another Black college operated just one mile away. Tillotson College, a private institution renowned for its departments of education and music, had served the East Austin community since it was chartered in 1877. The two schools enjoyed a healthy rivalry and both contributed significantly to the social and civic life of East Austin. However, neither institution possessed sufficient resources to provide the best education possible for their students. Confronted with this fact, Elliott pondered the question: why have two struggling Black colleges in the same city? Both schools had similar constituencies, curriculum shaped by moral and religious instruction, and a deep commitment to community service.6 Cognizant of these similarities, Elliott became a “moving force” in the merger of Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College.7 During a meeting of trustees on January 26, 1952, an agreement was reached to consolidate the two schools. A new charter was signed on October 24th of the same year and the newly minted Huston-Tillotson College became the exclusive provider of higher education for African Americans in Central Texas.8 3 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 4 Ora Houston, interview by Terri Myers, September 28, 2024. 5 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 6 “HT History,” Huston-Tillotson University, accessed June 23, 2025, https://htu.edu/about/history/#:~:text=The%20roots%20of%20Tillotson%20College,classes%20on%20January%20 17%2C%201881. 7 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 8 “HT History,” Huston-Tillotson University, accessed June 23, 2025, https://htu.edu/about/history/#:~:text=The%20roots%20of%20Tillotson%20College,classes%20on%20January%20 17%2C%201881. 5 It was said that Elliott “bore the burden in the heat of the day,” serving Huston-Tillotson College “during its years of struggle and hardships.”9 During his time at the newly merged institution, Elliott’s official duties included business manager, Associate Professor of Business Administration, and college accountant.10 He was also the treasurer of a citizen’s committee that supported the United Negro College Fund, a fund that enabled 32 private colleges and universities to give more scholarship aid, buy books and equipment, and pay teaching salaries.11 Finally, Elliott served as a member of the school’s Board of Trustees for fifteen years, after which he was made a lifetime honorary trustee. Elliott’s service to the college was officially recognized in 1979, when he was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Huston-Tillotson.12 O.H. Elliott (on the far left) pictured among Sam Huston footballers and coach as they wave goodbye in preparation to take off for Mexico City to play the Mexican National Polytechnical Institute in 1951.13 Photo of O.H. Elliott provided by his daughter Ora Houston 9 Ibid. 10 “More Than 250 Students Listed in H-T Classes,” Austin-American Statesman, June 16, 1955, p. 19. 11 “Austin Church Support Asked in Negro Drive,” The Austin American, May 28, 1951, p. 25. 12 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 13 “Waving Farewell,” The Austin American, Sept. 21, 1951, p. 24. 6 Though he was said to have a quiet, almost gentle demeanor,14 Elliott was not content to remain on the sidelines of advancement for African Americans during the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, as early as 1941, he headed a committee to ask for Black representation in elections within the Democratic Party, a request that was denied on the basis of the party’s mission statement to allow only white members to vote in its elections.15 However, this rebuff did not dissuade him from pursuing racial equality in the ensuing decades. It was not until three years later, in the landmark case Smith vs. Allwright (1944), that the Supreme Court reached the decision that Blacks could not be prohibited from voting in the Democratic primary even by party officials.16 Although this court decision formally abolished the white primary in Texas, attempts to limit Black political participation did not cease.17 In 1948, Elliott spoke at a political rally sponsored by the Negro Citizens Council aimed at bolstering political engagement among Black Austinites. The keynote speaker, Dr. Everett Givens, lauded the crowd: “your presence here shows your increased awareness of your rights and privileges in the government” and reminded them of their duty to inform themselves of the “issues of the day and the fitness of the candidates seeking office.”18,19 Elliott went on to embody this vision through active political engagement at both the local and state levels, holding leadership roles in the United Political Organization and the East Austin Council of Community Affairs,20,21 representing his community as a delegate to several State Democratic Conventions,22,23 and pursuing elected office as a candidate for Precinct Chairman in 1966.24 After Lyndon B. Johnson was inaugurated in 1964, he initiated a series of domestic programs known as “The Great Society” aimed at eliminating poverty and racial injustice in the United States. Great Society policy areas stretched far and wide: Civil rights, social and economic welfare, education, healthcare, and housing, among other spheres. Elliott seized upon this political climate and the resources it offered to “enhance the quality of life not only for [people] in Texas but for the disadvantaged throughout the United States of America.”25 14 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 15 “Negro Vote Is Ruled Out Here,” The Austin American, Jul. 22, 1942, p. 5. 16 Sanford G. Greenberg. “The Fight Against the White Primary in Texas: A Historical Overview,” Texas State Historical Association, Last updated September 29, 2020. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/white- primary 17 Sanford G. Greenberg. “The Fight Against the White Primary in Texas: A Historical Overview,” Texas State Historical Association, Last updated September 29, 2020. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/white- primary 18 “Negro Council to Sponsor Political Rally Tonight,” The Austin American, Jul. 21, 1948, p. 8. 19 “‘Howdy-Do Stage Takes Over Race,” Austin American-Statesman, Jul. 22, 1948, p. 8. 20 “State Negro Group for Rights Panel,” Austin American-Statesman, Dec. 22, 1964, p. 6. 21 “OEO Grant Sought By Eastside Group,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 25, 1966, p. 10. 22 “Travis County Delegate to Attend State Democratic Convention,” The Austin-American, Sept. 16, 1962, p. 6. 23 “Delegate Named to Demo Session,” Austin American-Statesman, Sep. 30, 1970, p. 17. 24 Democratic Party Primary Election,” The Austin American, June 2, 1966. 25 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 7 Through the inner workings of state and local government, Elliott worked “behind these scenes” to promote civil rights.26 He was one of the directors of the “Rights Agency” that encouraged the City Council to ask for the appointment of a human rights commission to ensure the effective implementation of the Civil Rights Law of 1964.27 This law is seen by many historians as one of the crowning achievements of the Great Society in that it translated the demands of the civil rights movement into policy.28 Elliott was also a member of the United Political Organization (UPO), a “Negro political group” that encouraged Governor Connally to include a provision for a state civil rights committee in his recommendations to the Legislature that same year.29 The UPO adopted an action program the following year that included poll tax payment drives, efforts to familiarize local areas of opportunities under the federal anti-poverty program, and good representation at the inauguration of Connally and President Lyndon B. Johnson.30 Elliott also led several local initiatives to honor civil rights leaders in Austin. In 1962, he presented a resolution to the City Council to rename Oak Springs Park after Dr. Givens, an East Austin dentist and civic leader.31 In 1966, Elliott was listed in The Austin American among “three of the eastsides’ most respected men” who handed the City Council a petition that a library moving to Oak Springs be renamed “George Washington Carver Library.”32 Both proposals were successful. Elliott also worked with the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), a Great Society initiative established to oversee a variety of community-based anti-poverty programs. As part of the East Austin Council of Community Affairs, Elliott helped push for an OEO grant for a Small Business Development Corporation (SBDC) in 1965. When the council was told that it might be years before Austin received a grant, they continued to organize. The chairman of the SBDC reported: “This would put a lot of people in business who would never get in any other way. We plan to apply and keep the pressure on everywhere we can in hope we’ll get the money earlier than scheduled.” The previous year, Elliott had arranged an Austin visit for James A. Madison, Deputy Chief of Community Relations for the Job Corps in the OEO. Elliott organized for Madison to talk at Anderson High School and Huston-Tillotson as well as attend a Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Mass Meeting in Pan-American Center.33 Elliott can also be found at the center of various efforts to ensure more equitable housing and healthcare in Austin. For instance, he was a driving force behind the first major low rent private housing development created in the City of Austin. In 1965, construction started on a $1.6 million apartment complex on a seven acre tract at Gunter-Springdale Road and Airport in East 26 Ora Houston, interview by Terri Myers, September 28, 2024. 27 “Rights Agency Bid By City Studied,” The Austin American, Jan. 8, 1965, p. 6. 28 Alan Brinkley, "Great Society" in The Reader's Companion to American History, Eric Foner and John Arthur Garraty eds., ISBN 0-395-51372-3, Houghton Mifflin Books, p. 472. 29 “State Negro Group for Rights Panel,” Austin-American Statesman, Dec. 22, 1964, p. 6. 30 Ibid. 31 “City Council Names Park After Dr. Givens,” Austin American-Statesman, Nov. 15, 1962, p. 6. 32 “Carver Library Pressed,” The Austin American, Mar. 11, 1966, p. 12. 33 “Camp Gary Tour Seen By Official,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 13, 1965, p. 9. 8 Austin.34 The project, organized by the St. Joseph Grand Lodge, was completely underwritten by a Federal Housing Authority (FHA) loan.35 Elliott, spokesman for the Lodge and part of the complex’s 3-member board of trustees, reported that the apartment would be geared towards low to moderate income families and include a daycare center and playground.36 In 1970, Elliott was part of a committee organized to investigate health administration in Travis County with a special focus on the care of indigent persons. Findings were presented to Travis County Commissioners Court and the City Council.37 Over the years, Elliott cultivated close relationships with President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governors John Connally, Preston Smith, and Dolph Briscoe, and U.S. Representative Jake Pickle.38 Because of his outstanding service to education and the state, Governor Connally named him to the Coordinating Board of the Texas College and University System in 1969.39 He was the first African American to serve on the Coordinating Board, a position he held until 1977. During his time on the board, Elliott cast the deciding vote to maintain the Law School at Texas Southern University. While Elliott’s work at Huston-Tillotson College and on the Coordinating Board might be his most celebrated achievements, he contributed to Austin civic life in countless additional ways. He was a man of faith who was deeply committed to his church, Wesley United Methodist Church, where he served as Chairman of the Trustee Board and as a delegate to the Methodist General Conference, among other positions within the congregation. Elliott’s community service was boundless. He was a 33rd degree Mason, a Shriner, and a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; a member of Connecting Links, the National Business League, and the Capital City Lion’s Club. He also served as a member of the Austin Housing Authority’s Finance Committee and the Austin Parks and Recreation Board, 40 and helped lead the Harry Lott division of the Boy Scouts of America. 41, 42 Over the years, Elliott participated in a number of philanthropic efforts. For instance, he helped plan a 1947 March of Dimes fundraising ball,43 raised money for the Red Cross as a member of the East Austin Chest Big Gifts Committee between 1947-1951,44, 45, 46 34 “Lodge To Develop 19-Unit Complex,” Austin American-Statesman, Oct. 28, 1965, p. 21. 35 The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) was created in 1934 as part of the New Deal and thus, was not a Great Society program. However, the Great Society expanded and built upon existing programs like the FHA to address broader social and economic issues. The FHA became part of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), a Great Society initiative established in 1965. 36 “Lodge To Develop 19-Unit Complex,” Austin American-Statesman, Oct. 28, 1965, p. 21. 37 Travis Committee View Area Health,” The Austin American, Jan. 30, 1970, p. 6. 38 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 39 “3 Austinites Among College Board Appointees, Austin American-Statesman, Jan. 12, 1969, p. 14. 40 Ibid. 41 “Scout Support,” The Austin American, June 1959, p. 20. 42 “DA to Speak Before Scouters,” Austin American-Statesman, Jan 21, 1960, p. 20. 43 “Negroes to Sponsor F.D.R. Birthday Ball to Help Polio Fund,” The Austin American, Jan. 20, 1946, p. 4. 44 “Red Cross Edges Past Drive Half-Way Mark,” Austin American-Statesman, Mar. 13, 1947, p. 15. 45 “More Pledges Roll In,” Austin American-Statesman, Nov. 6, 1950, p. 11. 46 “Veteran Who Knows Praises the Red Cross,” The Austin American, Mar. 8, 1951. 9 headed a Special Donations Voluntary Donations Committee to collect funds for a new animal shelter in 1956,47 and led a 1962 push to promote recreation in the Rosewood community.48 The impact that Elliott made on civic life in Austin cannot be overstated. Perhaps his most significant and enduring achievement was his role in the establishment of Austin Community College.49 Elliott was instrumental in bringing ACC to fruition through his adamant support and promotion of the college while serving on the Coordinating Board of Texas Colleges and Universities. It was an accomplishment hailed by the board president as “an absolute necessity to public and higher education in Central Texas.”50 Elliott’s role in founding ACC was so vital that the college dedicated its first commencement in 1977 to him in appreciation.51 In 1959, O.H. Elliott was vice chairman of the Harry Lott District of the Boy Scouts of America. He is pictured here receiving a check from the Austin Branch of the National Alliance of Postal Employees that will be used to send five boy scouts to Camp Wooten.52 O.H. Elliott, grand secretary of the St. Joseph Grand Lodge, presents a $69 check for the lodge to the Dental Clinic at 1183 Chestnut to buy toothbrushes for children.53 47 “Humane Society Opens Campaign for $16,000,” Austin American-Statesman, June 11, 1956, p. 8. 48 “Recreation Talks Called For Center,” The Austin American, Dec. 2, 1962, p. 43. 49 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 50 “October Hearing Announced For New Community College,” The Austin American, Sep. 28, 1972, p. 24. 51 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 52 “Scout Support,” The Austin American, June 1959, p. 20. 53 “Money for Clinic,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 21, 1966, p. 7. 10 O.H. Elliott (fourth left to right) pictured among members of the East Austin Community Big Gifts Committee.54 In 1963, O.H. Elliott was presented with an outstanding achievement award from the Masonic body.55 Family Not long after Elliot initially arrived in Austin to work at Samuel Huston College, he met Thelma Mitchell of San Antonio and the two were married in her hometown on January 6, 1938. The couple had two daughters, Ora Ann and Thelma Karen.56 In 1954, the Elliotts bought a home at 2207 East 22nd Street in what was then referred to as the “Negro District,” located south of Manor in East Austin. Described by their daughter Ora Ann as a “complete community,” their neighborhood was economically diverse and composed of Black-owned homes and businesses.57 Over the ensuing decades, the Elliott home became a gathering space for the community, hosting a variety of church, political, and civic meetings conducted by both Elliott and his wife, another East Austin mover and shaker. Thelma Mitchell Elliott Thelma Mitchell was born on November 25, 1912 in San Antonio, Texas. She attended Douglass High School and then moved to Austin, where she received her undergraduate degree from Samuel Huston College and later served as Assistant Dean of Women at Clark College.58 In the early 1950s, Mrs. Elliott returned to school in order to pursue a career in social work. She was among the “precursors,” the first generation of Black students who desegregated the University of Texas at Austin in the 1950s. The struggle for desegregation at UT had begun much earlier, when an African American man applied and was denied on the basis of his race in 1885, only 54 “More Pledges Roll In,” Austin American-Statesman, Nov. 6, 1950, p. 11. 55 “Honored,” Austin American-Statesman, Aug. 14, 1963, p. 16. 56 Ibid. 57 Ora Houston, interview by Terri Myers, September 28, 2024. 58 “ENABLE: More Than An Anti-Poverty Committee,” The Austin American, June 12, 1966, pg. 10 11 two years after the university’s founding. Sixty-five years later, in the fall 1950, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Heman Marion Sweatt’s application to UT’s law school. That same fall, the University of Texas opened its graduate program in social work. Within two years, the first African American students graduated from the school: Gus Swain was the first male graduate in 1953, and Thelma Elliott was the first female graduate in 1954. “Precursors” such as Swain and Mrs. Elliott attended classes amidst threats of violence, intense scrutiny, and widespread hostility. Swain, in a 1982 speech, recalled that the School of Social Work felt like an “oasis” in the tense atmosphere of early desegregation.59 After receiving her Master of Science in Social Work, Mrs. Elliott began a ten-year stint as the first Black female probation officer for the Travis County Juvenile Court. She also served as a social worker at Brackenridge Hospital, an instructor at Samuel Huston, president of the PTA, and was involved in her church.60 In addition, Mrs. Elliott juggled family responsibilities as the wife of O.H. Elliott, then business manager at Samuel Huston College, and mother of two daughters, Ora Ann and Thelma Karen. Ora Houston recalled that her mother “had a very deep sense of social justice.”61 Mrs. Elliott’s commitment to social justice impacted not only her career choice but how she raised her family. Ora Houston recalled that their house “was always about service.”62 Ora’s involvement in her community from an early age reflects this: In 1951, at the age of eight, Ora sang at a Christmas program among children and grandchildren of the Douglass Club, a women’s organization affiliated with National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.63 In high school, she was a member of the Future Nurses Club,64 was recognized in The Austin American for volunteering at a flood refugee shelter,65 and was among the seniors at Anderson High who received the most “good citizenship certificates.”66 “I tell people all the time that I have my mother’s sense of social justice,” Ora said. “She was not a rebel, she was not out there marching on the streets. But in her own quiet way, she made important changes.”67 Perhaps some of the most important changes that Mrs. Elliott made were through her work with ENABLE. In 1966, in recognition of her work in Juvenile Court, Elliott was tapped to lead project ENABLE, as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. ENABLE (Education and Neighborhood Action for Better Living Environment) was sponsored by Child and Family Services and funded through the new Office of Economic Opportunity, the federal agency in 59 Andrea Campetella, “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty,” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. 60 Ibid. 61 Ora Houston, interview by Terri Myers, September 28, 2024. 62 Ibid. 63 “Douglass Club Relatives Give Christmas Program,” Austin American-Statesman, Dec. 20, 1951, p. 36. 64 “Capping Service Set Today for Girls of High School Future Nurses Club,” The Austin American, Feb. 1, 1959, pg. 32. 65 “23 Students Pitch In for Flood Work,” The Austin American, Nov. 6, 1960, pg. 8. 66 “Good Citizen Program Set At Anderson,” The Austin American, Apr. 30, 1961, pg. 9. 67 Andrea Campetella, “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty,” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. 12 charge of administering many War on Poverty programs.68 In a Statesman article printed on May 19, 1966, Mrs. Elliott explained the mission of ENABLE as giving mothers “a sense of self, purpose, confidence and power, something that will grow, a motivation, and the tools to get something done for a better life.”69 Austin Child and Family Service executive director, Richard Standifer, reported that “many poverty families in Austin are not aware of either the long established resources in our city that are available to them,” “do not feel the services are for them,” or “lack the courage and know-how to seek such services and maintain the effort necessary to get them.”70 ENABLE sought to tackle this problem by providing a space in which parents could collaborate, learn about opportunities to improve their and their children' s lives, and as a result, “win a permanent increase in self-confidence and capacities as parents and community members in meeting responsibilities more effectively.”71 Ms. Elliott (second from right, in green dress) with ENABLE team members72 Low income families were often connected to ENABLE through other War on Poverty programs such as Head Start, however, a special effort was reportedly made to reach “the unreachable.” “We will knock on every door,” said Standifer.73 ENABLE also provided free transportation and childcare to residents who attended neighborhood group problem-solving meetings. After the 68 Ibid. 69 “ENABLE: More Than Anti Poverty Committee,” The Austin American, June 12, 1966, pg. 10. 70 Ibid. 71 Ibid. 72 Photo AR-2007-017-033, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library 73 Ibid. 13 first such meeting, Mrs. Elliott reported: “This is so new it will take a while to catch on. But we did focus on many problems of the family and community. They told me they had wanted to talk about these things before but did not know where to go or how to go about it.”74 Under Mrs. Elliott’s leadership, ENABLE evolved into group problem-solving initiatives to tackle specific problems such as unsanitary living conditions in rental units to neighborhood safety and infrastructure. Though some of the work may seem modest today, ENABLE had a demonstrated positive impact on the health and well-being of primarily Black and Mexican communities throughout Austin. Before ENABLE, residents of Hergotz Lane in the southeastern part of the city had to travel 10 miles to the nearest supply of drinking water. Under Mrs. Elliott's leadership, in May of 1966, they celebrated the installation of a water spigot in the neighborhood.75 It was just a single, public spigot, but it solved a long-needed problem. A month later, in June, three men under the auspices of ENABLE waged war against mosquitoes in Montopolis with the aid of a fogging machine. Perhaps inspired by their success, Montopolis residents fought and won a battle for public transportation to connect them to city bus lines later that month. In September, ENABLE encouraged the formation of the Parents Club of Booker T. Washington Terrace public housing complex. The club organized a cleanup day in which parents and children cut down the high grass in the playground and removed bottles and rocks.76 Water spigot on Hergotz Lane77 Mrs. Elliott at the Booker T. Washington Terrace public housing78 74 Ibid. 75Andrea Campetella, “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty,” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. 76Andrea Campetella, “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty,” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. 77 Photo AR-2007-017-069, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library. 78 Photo AR-2007-017-045, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library 14 Also in September, ENABLE appeared in the Statesman urging Travis County residents experiencing job discrimination to contact the Austin Equal Citizenship Corporation. According to one committee member, Montopolis residents complained that they didn’t get fair chances at jobs and promotions, and some kids still quit school because they believe all they can ever get is a “pick and shovel job.” Having identified this issue at neighborhood meetings, ENABLE sought actionable ways to rectify it.79 As a whole, ENABLE’s work was never abstract; it was concrete, collaborative, and rooted in the lives of real people. By helping communities organize and act, ENABLE helped restore a sense of dignity and power where it had long been denied. Within a year of its launch, ENABLE Austin was recognized as one of the most successful of 60 such projects around the country.80 Felton Alexander, area coordinator of ENABLE, said that the dialogue between staff and committee members was more effective and open than any other he had witnessed.81 Mrs. Alline Del Valle, six-state Houston-based area supervisor, credited the Austin program as having the best referral system of any city in the 20-city area. “It was thrilling to see the people ready to move. One of the men said they had tried before to get things done but he can see now they didn’t know how,” said Del Valle after attending a meeting in Montopolis.82 Without a doubt, much of ENABLE Austin’s early success can be traced to the steadfast leadership of Mrs. Elliott. When she resigned as director after nine months in order to accept a role at the Texas Office of Economic Opportunity (TOEO), the Brooksdale Improvement Club wrote to her: “We have heard that you have resigned. We hope this is not true, but if it is, we hope you will remain in a leadership role in helping others as you have helped us.”83 Her departure marked a bittersweet moment for East Austin, however, her new role at the state level meant her influence would stretch even further. In December of 1966, Mrs. Elliott started her new position as the Research and Program Specialist in the Community Action Division of the TOEO. “We feel that Mrs. Elliott’s long experience working with low-income families qualifies her highly for this state-level assignment in the war on poverty,” said director Walter Richter.84 Mrs. Elliott was tasked with planning and developing resource materials, ideas, and techniques for use by TOEO consultants and Community Action Program directors throughout the state.85 While this work proved invaluable, it also unfolded during a time of growing national tension, as the escalation of the Vietnam War led to shrinking federal budgets for domestic programs. The War on Poverty, once a centerpiece of national policy, began to lose momentum.86 As funding dried up and federal support waned, Mrs. Elliott’s ability to contribute through this role was 79 “Job Discrimination Claims Due Equal Citizenship Corp.,” Austin American-Statesman, Sep. 14, 1966, pg. 14. 80 “Mrs. Elliott Added to the OEO Staff,” The Austin American, Dec. 16, 1966, pg. 2. 81 “ENABLE: More Than Anti Poverty Committee,” The Austin American, June 12, 1966, pg. 10. 82 “Poverty Program Rates High,” The Austin American, June 9, 1966, p. 5. 83 “Mrs. Elliott Added to the OEO Staff.” The Austin American, Dec. 16, 1966, p. 2. 84 Ibid. 85 Ibid. 86 Ryan Larochelle. “A Mission Without Precedent: The Rise and Fall of the Office of Economic Opportunity, 1964- 1981,” Journal of Policy History 36, no. 1 (2024). https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/122/article/916370#info_wrap 15 curtailed. Still, her commitment to social justice never wavered. She continued to serve the community as the Director of Social Services with the Mental Health and Mental Retardation Center and later with the Texas Department of Human Services, where she ultimately retired.8788 Lives of Service Both O.H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott were tireless advocates for civil rights, education, and human dignity—each forging their own path but united by a shared commitment to justice and community empowerment. O.H. Elliott worked within institutions, breaking barriers in higher education and wielding political influence to open doors for others. Thelma Elliott, rooted in the social work tradition, championed community-driven solutions, empowering East Austin families through programs like ENABLE that listened to and uplifted their voices. Together, they worked in a system that had long excluded their community, doing the difficult, often invisible work that brought real change and restored agency to those long denied it. After a lifetime of steadfast commitment to their community, O.H. Elliott passed on February 21, 1984, and Thelma Mitchell Elliott passed on July 21, 1998.89, 90 Their legacy lives on in Austin through their daughter, Ora Ann Houston, who inherited their conviction, compassion, and dedication to the community. Just like her parents, Ora Houston has led a life oriented around public service and civic engagement. Raised by two leaders who worked to amplify the voices of East Austin residents, Houston learned early the power of listening—to ask questions before offering answers, to lead by walking alongside.91 These skills served her well in her 27 years working with the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and Child Protective Services. Even in retirement, she remained committed to public service, working in the office of Texas Senator Gonzalo Barrientos from 1999-2003 and serving as the first representative of District 1 on the Austin City Council between 2015 to 2019. While on City Council, she helped found Austinites for Geographic Representation, ensuring that communities like hers could elect leaders who reflected their lived experience.92 Houston’s commitment to her community extends far beyond her official titles. She is an active member of St. James Episcopal Church, an inclusive, multi-cultural community of faith. In addition, Houston has served on a number of commissions and councils,93 lent her voice to 87 “Crisis Care Needs Listed,” The Austin American, May 2, 1968, pg. 46. 88 Andrea Campetella, “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty,” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. 89 “Death and Funerals: O.H. Elliott,” Austin American-Statesman, Feb. 2, 1984, p. 14. 90 “Funerals and Memorials: Thelma Mitchell Elliott,” Austin American Statesman, July 24, 1998, p. 22. 91 “Women We Love: Ora Houston,” Austin Monthly, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.austinmonthly.com/women-we-love-ora-houston/ 92 “About Ora Houston,” Ora Houston, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.oraatx.com/about-ora 93 Ora Houston was a member of the Citizens Advisory Task Force of the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan, the collaborative council of the Travis County Model Court for Children and Families, and the Disproportionality Committee of Family and Protective Services. She was also vice-chair of the Upper Boggy Creek Neighborhood Planning Team. 16 planning teams, and stayed present on the streets of the neighborhood she called home. “If I’m afraid of the people I represent,” she once said, “then I don’t need to be on the council.” It is this unshakable belief in proximity, compassion, and accountability that has earned Houston a number of awards— the Pioneer Spirit Award, Outstanding Women in Texas Government (1998), Public Citizen of the Year, Texas Chapter, National Association of Social Workers (2009), Outstanding Civic Engagement, Austin Branch, NAACP (2011), and outstanding alumni, Huston-Tillotson International Alumni Association (2012).94 That legacy remains rooted not only in her values but in place. Houston continues to live in the home her parents, O.H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott, built in 1954 on East 22nd Street. The house stands as a symbol of resilience, progress, and Black civic leadership in East Austin, a physical anchor for the multigenerational story of advocacy and empowerment the Elliotts began and their daughter carries forward. Photos of O.H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott provided by their daughter Ora Ann Houston 94 “About Ora Houston,” Ora Houston, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.oraatx.com/about-ora 17 Bibliography “3 Austinites Among College Board Appointees.” Austin American-Statesman. Jan. 12, 1969, p. 14. “About Ora Houston.” Ora Houston. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.oraatx.com/about-ora “Austin Church Support Asked in Negro Drive.” The Austin American. May 28, 1951. p. 25. Brinkley, Alan. "Great Society" in The Reader's Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John Arthur Garraty eds., ISBN 0-395-51372-3. Houghton Mifflin Books, p. 472. Campetella, Andrea. “A Social Work Precursor: Thelma Mitchell Elliott, Desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty.” The Utopian, Sep. 24, 2018. https://sites.utexas.edu/theutopian/a-social-work-precursor/ “Camp Gary Tour Seen By Official.” Austin American-Statesman. Feb. 13, 1965. p. 9. “Capping Service Set Today for Girls of High School Future Nurses Club.” The Austin American. Feb. 1, 1959. p 32. “Carver Library Pressed.” The Austin American. Mar. 11, 1966. p. 12. “City Council Names Park After Dr. Givens.” Austin American-Statesman. Nov. 15, 1962. p. 6. “Crisis Care Needs Listed.” The Austin American. May 2, 1968, pg. 46 “DA to Speak Before Scouters.” Austin American-Statesman. Jan 21, 1960. p. 20. “Delegate Named to Demo Session.” Austin American-Statesman. Sep. 30, 1970. p. 17. “Democratic Party Primary Election.” The Austin American. June 2, 1966. “Douglass Club Relatives Give Christmas Program.” Austin American-Statesman. Dec. 20, 1951. p. 36. “ENABLE: More Than Anti Poverty Committee.” The Austin American. June 12, 1966. p. 10. “Funerals and Memorials: Thelma Mitchell Elliott.” Austin American Statesman. July 24, 1998, p. 22. 18 “Good Citizen Program Set At Anderson.” The Austin American. Apr. 30, 1961. p. 9. Greenberg, Sanford G. “The Fight Against the White Primary in Texas: A Historical Overview.” Texas State Historical Association. Last modified September 29, 2020. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research and citation/chicago manual 17th edition/cmos fo rmatting_and_style_guide/web_sources.html “Honored.” Austin American-Statesman. Aug. 14, 1963. p. 16. “‘Howdy-Do’ Stage Takes Over Race.” Austin American-Statesman. July 22, 1948, p. 8. “HT History.” Huston-Tillotson University. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://htu.edu/about/history/#:~:text=The%20roots%20of%20Tillotson%20College,class es%20on%20January%2017%2C%201881. “Humane Society Opens Campaign for $16,000.” Austin American-Statesman. June 11, 1956. p. 8. “Job Discrimination Claims Due Equal Citizenship Corp.” Austin American-Statesman. Sep. 14, 1966. pg. 14. Larochelle, Ryan. “A Mission Without Precedent: The Rise and Fall of the Office of Economic Opportunity, 1964-1981,” Journal of Policy History 36, no. 1 (2024). https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/122/article/916370#info_wrap “Money for Clinic.” Austin American-Statesman. Feb. 21, 1966. p. 7. “More Pledges Roll In.” Austin American-Statesman. Nov. 6, 1950. p. 11. “Mortuary Sets Open House,” The Austin American. Austin: May 13, 1971. p. 27. “Mr. and Mrs. John T. King Announce ‘Open House,’ The Austin American. Austin: February 6, 1960. p. 11. “Mrs. Elliott Added to the OEO Staff.” The Austin American. Dec. 16, 1966. p. 2. “Negro Council to Sponsor Political Rally Tonight.” The Austin American. July 21, 1948, p. 8. “Negroes to Sponsor F.D.R. Birthday Ball to Help Polio Fund.” The Austin American. Jan. 20, 1946, p. 4. 19 “Negro Vote Is Ruled Out Here.” The Austin American. Jul. 22, 1942, p. 5. “October Hearing Announced For New Community College.” The Austin American. Sep. 28, 1972. p. 24. “OEO Grant Sought By Eastside Group.” Austin American-Statesman. Feb. 25, 1966. p. 10. “Poverty Program Rates High.” The Austin American. June 9, 1966. p. 5. “Recreation Talks Called For Center.” The Austin American. Dec. 2, 1962. p. 43. “Red Cross Edges Past Drive Half-Way Mark.” Austin American-Statesman. Mar. 13, 1947. p. 15. “Rights Agency Bid By City Studied.” The Austin American. Jan. 8, 1965. p. 6. “Scout Support.” The Austin American. June 1959. p. 20. “State Negro Group for Rights Panel.” Austin American-Statesman. Dec. 22, 1964. p. 6. “St. John’s: Transit Problem Develops.” Austin American-Statesman. Nov. 15, 1966. p. 3. “Travis Committee View Area Health.” The Austin American. Jan. 30, 1970. p. 6. “Travis County Delegate to Attend State Democratic Convention.” The Austin-American. Sept. 16, 196., p. 6. “Veteran Who Knows Praises the Red Cross.” The Austin American. Mar. 8, 1951. “Waving Farewell.” The Austin American. Sept. 21, 1951. p. 24. “Women We Love: Ora Houston.” Austin Monthly. Accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.austinmonthly.com/women-we-love-ora-houston/ 20 O.H. and Thelma Mitchell Elliott House – 2207 E. 22nd Street, Austin, TX 78722 Color Digital Photos – original labeled prints submitted separately Photo 1: North (primary) façade, camera facing south Photo 2: North façade and Inset Porch, camera facing southeast Photo 3: East and North facades, camera facing southwest Photo 4: West façade, camera facing southeast Photo 5: South (rear) façade, camera facing north Photo 6: Carport and Shed, East and North facades, camera facing south/southwest Photo 7: Front porch, North and East Walls, camera facing west Photo 8: Front Entrance, North façade, camera facing south Photo 9: Carport, North & West house facades, camera facing south Photo 10: Front-gabled East Wing, North façade, camera facing south/southeast Photo 11: Interior – Kitchen with Original Stove Photo 12: Mobile Home West façade, camera facing northeast https://www.newspapers.com/image/384969276/ The Austin American (Austin, Texas) · Sun, Dec 12, 1954 · Page 68 Downloaded on Oct 16, 2025 Copyright © 2025 Newspapers.com. All Rights Reserved. ART WORKS Art and community in Mart, Texas A SOCIAL WORK PRECURSOR Thelma Mitchell Elliott, MSSW '54 RENACER IN OAXACA Partnerships for maternal health THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN | STEVE HICKS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK FALL 2018 Art Works, p. 2 "IN A SENSE, MY PARENTS WERE LUCKY THAT THEIR INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE WAS DISMISSED AS SOMETHING 'PUERTO RICANS DO.' DURING OUR COUNTRY'S PAINFUL PERIOD OF LEGALLY ENFORCED RACIAL SEGREGATION, OTHERS WERE NOT SO LUCKY." FROM THE DEAN I t was my father’s aspiration to forge a future for his children that led to his enlistment in the U.S. Army. In 1956, after the Korean War, his assignment took us from a small town in Puerto Rico to a new home in Richmond, Virginia. My father was a dark-skinned biracial Puerto Rican (white father, black mother), and my mother was white. Their interracial marriage was rather typical in the island, and I didn’t think much of it. Years later I understood that their marriage was rather remarkable in the mainland. I asked my mother one day about their arrival in Virginia, a state where “miscegenation” was actually a felony. She replied matter-of-factly, “Oh, as soon as people heard your father and me speaking Spanish, they brushed it off. To them we were foreigners, and they thought that’s what ‘they’ do.” In a sense, my parents were lucky that their interracial marriage was dismissed as something “Puerto Ricans do.” During our country’s painful period of legally enforced racial segregation, others were not so lucky. Many fought, in many ways, for the end of legalized segregation. I have shared in other communications that our building used to house a junior high school that led desegregation in Austin. This issue brings you the story of Thelma Mitchell Elliott, a graduate from our program and one of the Precursors, the first generation of black students that desegregated the university in the early 1950s. Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964, segregation and discrimination against people of color and vulnerable populations persist — we see it in police shootings of African American men; detention and separation of asylum-seeking families; the consequences of eating, barbecuing or doing ordinary things “while black.” Social workers fight against these acts daily with our profession’s variegated skills and tools. Sometimes, as you will read in this issue, this fight involves using art and creativity to recover forgotten histories and build community. Other times, it involves crossing disciplinary and geographic borders to create positive change. I am proud that our faculty, students and alumni bring every skill to bear on making our world a more just one. Luis H. Zayas Dean and Robert Lee Sutherland Chair in Mental Health and Social Policy FROM YOU (ON “ALWAYS ON DUTY”) @nursingjobshcrs @phallv “Love stories like this!” “Good informative article.” @Aggie_GR “That’s awesome and a great reminder that Texas’ two largest research universities, TAMU and UT Austin, are jointly committed to supporting our veterans and their families!” @Galagator89 “One of the many reasons I am proud to be part of the @ UTSocialWork. The professors continue to teach the importance of research, how it can lead to creating interventions that can help individuals and the world. Thanks for sharing.” ALWAYS ON DUTYMilitary spouses tell their storiesHOPE AFTER TRAUMAIn Katrina’s and Harvey’s wakeON CAMERAProsecuting domestic violenceSPRING 2018THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN | STEVE HICKS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORKMilitary spouses tell their stories p. 2 CONTENTS 2 ART WORKS How Paula Gerstenblatt used art as a tool for community building and change in Mart, Texas. 10 18 A SOCIAL WORK PRECURSOR Thelma Mitchell Elliott, desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty in Texas. RENACER IN OAXACA Building partnerships across borders for better maternal health. e h t utopian The Utopian is published for alumni and friends of The University of Texas at Austin Steve Hicks School of Social Work. Steve Hicks School of Social Work Dean Luis H. Zayas Editor & Director of Communications Andrea Campetella Photography Lynda Gonzalez Art Direction & Design UT Marketing & Creative Services (Ryan Goeller, Christine Yang, Laurie O’Meara and Von Allen) This Issue’s Contributors Laura Turner Katherine Corley Fall 2018 | Vol. 18 No. 2 7 Ask the Expert Amy Thompson on migrant children 8 Without Borders Research from students in the dual degree with Latin American Studies 14 @socialwork Ideas, findings, people 20 Class Notes 22 First Person Finding oneself through hip hop 23 Community /UTSocialWork @UTSocialWork sites.utexas.edu/theutopian Please send comments, news items, suggestions and address changes to: The Utopian Editor Steve Hicks School of Social Work The University of Texas at Austin 1925 San Jacinto Blvd., Stop D3500 Austin, TX 78712-1405 Email: utopian@utlists.utexas.edu Phone: 512-471-1458 All submissions are subject to editing and are used at the editor’s discretion. Opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect official school and/or university policy. Articles might be reprinted in full or in part with written permission of the editor. Your comments are welcome. STE VE HICKS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK 1 PHOTO AR-2007-017-046, AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY 10 THE UNIVERSIT Y OF TE X AS AT AUSTIN In September 1966, the Parents Club of the Booker T. Washington Terrace public housing organized a cleanup day. Thelma Mitchell Elliott, desegregation at UT Austin, and the War on Poverty in Texas In May of 1966, residents of Hergotz Lane in South East Austin celebrated the installation of a water spigot in their neighborhood. It was just a single, public spigot, but it meant that they no longer had to travel 10 miles to the nearest drinking water supply. In early June, “a task force of three men and a fogging machine,” as the Austin Statesman put it, descended on Montopolis to wage war on mosquitoes. Later that month, after a hard battle for access to public transportation, Montopolis families were able to board a bus that connected them to Austin bus lines. And in September, the newly minted Parents Club of the Booker T. Washington Terrace public housing organized a cleanup day. Parents and children cut down the high grass in the complex’s playground and removed trash, bottles and rocks. By Andrea Campetella / Photos Courtesy Austin History Center STE VE HICKS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK 11 a social work PRECURSOR [THELMA ELLIOTT] WAS AMONG THE PRECURSORS, THE FIRST GENERATION OF BLACK STUDENTS WHO DESEGREG- ATED THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN IN THE 1950s. This flurry of activity in mostly Mexican and African-American areas of Austin owed much to the late Thelma Mitchell Elliott (MSSW ’54). Elliott was the leader of ENABLE, one of the many programs through which the Lyndon B. Johnson administration waged the War on Poverty across the nation. Under Elliott’s leadership, ENABLE empowered diverse communities in Austin to tackle everything from living conditions to neighborhood safety and infrastructure. But even before Elliott was publicly recognized for this important work, she did something else that, at the time, went unrecorded. She was among the Precursors, the first generation of black students who desegregated The University of Texas at Austin in the 1950s. Integration at UT Austin As told in As We Saw It. The History of Integration at The University of Texas at Austin, the struggle to desegregate the university started only two years after it was founded, when in 1885 an African-American man (unnamed in the records) applied for admission. He was rejected on the basis that “admittance of negroes” was “not of standard practice.” The turning point was after World War II. In 1946, with the support of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Heman Marion Sweatt applied to the law school and was denied access on the basis of his race. The case (Sweatt v. Painter) went all the way to the Supreme Court, which in 1950 ruled in Sweatt’s favor. Amidst much media attention and demonstrations in favor and against desegregation, Sweatt started law school in the fall semester of that year. That same fall, the university’s newly minted graduate program in social work opened its doors to students. In its two first years, the program admitted the late Gus Swain — who in 1953 became the first African-American male graduate — and then Elliott, who in 1954 became the first African-American female graduate. In a speech Swain gave in 1982 he described going to campus with the threat of violence, at a time when buildings off the main drag were plastered with sayings like “Nigger go home.” But he also recalled that the school of social work felt like an “oasis” and a safe place during this time. Anita Swain, who was married to Gus Swain when he was in school, said in a phone conversation that “the school of social work was pretty liberal as far as race relations.” She also remembered her late husband as a fighter for equality. “He would not tolerate racial discrimination. He was a crusader. He was in the right field, always trying to make things better and help people move on. When we lived in Washington [after Swain graduated], we were marching every Saturday!" she recalled. I just kept my P h o t o A R - 2 0 0 7 - 0 1 7 - 0 4 5 , i A u s t i n H s t o r y C e n t e r , A u s t i n P u b l i i c L b r a r y 12 THE UNIVERSIT Y OF TE X AS AT AUSTIN OPPOSITE PAGE Elliott at the Booker T. Washington Terrace public housing. LEFT Elliott (second from right, in green dress) with ENABLE team members. BOTTOM Hergotz Lane residents using the public water spigot. motivation, and the tools to get something done for a better life,” Elliott explained in a Statesman article of May 19, 1966. ENABLE soon expanded into “neighborhood group problem-solving” initiatives that engaged community members to tackle everything from unsanitary living conditions in rental units to neighborhood safety and infrastructure. Barely a year after it was launched, ENABLE Austin was considered one of the most successful of 60 such projects that existed across the nation. Because of the program’s positive impact in communities such as Montopolis, in October 1966 Elliott was asked to address a national conference of Head Start teachers. In true social work fashion, Elliott chose to emphasize self-awareness and strength-based perspectives during her address. As reported in the Statesman, she told Head Start teachers to be aware of their own insensitivities and blind spots when working with families, and make efforts to involve and empower parents. “We in ENABLE are also committed to involving the parents in the education of their children. We encourage parents to use their native talents and constitutional rights to make decisions affecting them, their children, and the neighborhood where they live,” Elliott told the teachers. ENABLE IS MEANT TO GIVE [MOTHERS] A MOTIVATION, AND THE TOOLS TO GET SOMETHING DONE FOR A BETTER LIFE. In late 1966, Elliott left ENABLE to join the Texas Office of Economic Opportunity, where she was tasked with developing resource materials, ideas and techniques to be used in community projects across the state. As the War on Poverty and its accompanying federal funding dwindled down in the context of escalation of the Vietnam War, Elliott continued her career in social services. She first joined the Austin/Travis County public health system and then the Texas Department of Human Services, from which she eventually retired. She died on July 21, 1998. “I tell people all the time that I have my mother’s sense of social justice,” daughter Ora Houston said. “She was not a rebel, she was not out there marching on the streets. But on her own quiet way, she made important changes.” ■ boots ready because whether it was cold, or snowy or wet, we were going to march!” The Swains knew Elliott as a neighbor and family friend. Anita Swain remembered her husband giving Elliot information about the newly opened social work program and encouraging her to apply. At the time, Elliott was married to O. H. Houston, then a business manager at Sam Huston College. They had a young daughter, Ora Houston, who is now Austin’s Council Member for District 1. She still lives in the house in East Austin where she grew up. At least as remembered by Ora Houston, Elliott was not the marching type. But she was a multifaceted community leader for whom the graduate social work program was a great match. “She was president of the PTA; she was very involved in the community; she was very involved in the church… and she had a very deep sense of social justice,” Houston said. Project ENABLE and Beyond After receiving her Master of Science in Social Work in 1954, Elliott worked as a probation officer for the Travis County Juvenile Court until 1966, when she was tapped to lead project ENABLE. ENABLE stood for Education and Neighborhood Action for Better Living Environment. It was sponsored by Child and Family Services and received funding through the new Office of Economic Opportunity, the federal agency responsible for administrating most of the War on Poverty programs. In Austin, ENABLE started by reaching out to mothers of children enrolled in Head Start — another War on Poverty program. “ENABLE is meant to give them [the mothers] a sense of self, purpose, confidence and power, something that will grow, a Photo AR-2007-017-033, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library; Photo AR-2007-017-069, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library STE VE HICKS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK 13 DESEGREGATION at The University of Texas at Austin 1883 University opens its doors. 1885 First record of African American applicant (unnamed) denied admission. 1938 George L. Allen is able to register for a class but then his registration is canceled. 1946 Heman Sweatt is denied admission to the law school. Case (Sweatt v. Painter) goes to the Supreme Court. 1950 Supreme Court rules in Sweatt’s favor. UT becomes the first institution of higher education in the South required by law to admit African Americans to its graduate programs. 1956 First group of Black undergraduate students are admitted.