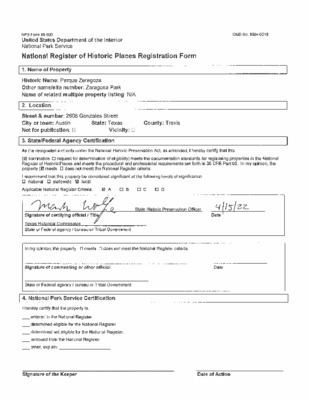

22.2 - Parque Zaragoza - NRHP form — original pdf

Backup